During a recent meeting, Stephen Emmel drew my attention to an article published by John Lawrence Sharpe in the proceedings of the International Conference on Conservation and Restoration of Archive and Library Materials, Erice, April 22nd-29th 1996.[1]

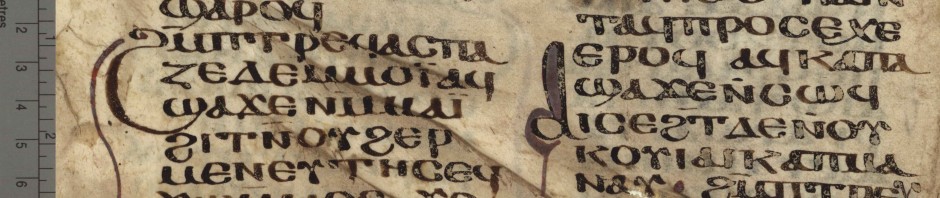

In his paper, Sharpe studied the binding of certain Coptic codices. What is interesting is that he managed to convince William M. Voelkle, curator and head of the Department of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts, to accept the radiocarbon testing of a piece from the binding of the Glazier Codex (Acts 1:1-15:3 in the Middle-Egyptian dialect of Coptic). As far as I am aware, the results of the testing have passed unnoticed by Coptologists and scholars interested in biblical manuscripts. Here is the passage in which Sharpe explains the experiment:

“In consultation with W. Voelkle of the Pierpont Morgan Library, a piece of the wrapping band of Morgan G.67 approximately 17mm.2 and .25mm thick was selected for analysis. A piece of the wrapping band was chosen because of all the possible replacements, the most likely would have been the leather of the bands – those elements which would be represented by those pieces which are least likely to have been replaced. So the terminus post quam for the latest binding would be represented by those pieces which are least likely to have survived and most likely to have been replaced. So on the 18th of April 1994, a piece of the leather wrapping band was sent to the Eidgenössiche Technische Hochschule in Zürich (Institute of Partial Physics) for analysis for the AMS 14C dating. On the 19th of May 1994, the report for the piece of leather was returned from Dr. Georges Bonani with the following report: from Lab. No. ETH-12270, a sample of leather produced the AMS 14C Age [y BP] of 1’565 ± 45 with the results of δ13C[o/oo] of – 23.6 ± 1.1 with the calibrated Age [BC/AD] of AD 420-598 […]” (p. 383 n. 13)

Of course, all one can sensibly say after the radiocarbon testing is that the latest possible date for codex Glazier’s binding is 598 CE. However, as the manuscript is in a very good state of preservation, I find unlikely that the binding has ever needed to be replaced. Being the case that Codex Glazier is similar, especially in terms of format, to certain manuscripts from the Monastery of Apa Jeremias at Saqqara (which can be dated ca. 600 CE), I would opt for a late 6th century dating.

[1] J.L. Sharpe, “The Earliest Bindings with Wooden Board Covers: The Coptic Contribution to Binding Construction.” In: Erice 96, International Conference on Conservation and Restoration of Archive and Library Materials, Erice (Italy), CCSEM, 22nd-29th April 1996: Pre-prints, edited by Piero Colaizzi and Daniela Costanini, 2:381-400. 2 vols. Rome: Istituto centrale per la patologia del libro 1996.

Radiocarbon dating always gives the date expected. See a contrario the so-called (¹) Codex “Tchacos”.

1. I hate this name.

What did I say ? Ah ! oui… « — What date range do you prefer for your artifact radiocarbon dating ? Ask one, and if, despite our efforts, our is not within it, it is unreliable (¹). »…

1. End of § 3.

Radiocarbon dating was also done for the Cologne Mani Codex in the 90’s. Don’t know if the results were published.

Hmm. Would this have implications, I wonder, for the production-date of the mae (Scheide) copy of Matthew?

Maybe double-check by sending it to the labs that tested the “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife.” They might give results that say the Glazier Codex is our oldest copy of Acts in any language.

I believe that Papyrus 45 still predates Glazier Codex by several centuries.

I agree, As a person with a degree in Archaeology i can say that Radiocarbon Dating needs to be calibrated according to the context that the artefact was found in, totally defying the point of dating in the first place. For the oldest manuscripts, try the Aramaic Peshitta and Khabouris, the content of which is internally dated and certified to belong to the early 2nd century AD, as almost-original as one can get.

Not really the *context where it was found*, or else people would not be spending their time and money on this. It’s the material that counts. Today there are standard calibration programmes that allow one to check such results. I am told that for leather with a C14 date of 1565 the date range give here is 95% certain, with a 4-5% chance of it being in the 20-30 years on either side. Note however that this dates the leather, not the production of the codex: whatever the date of the leather within this range, it is only a terminus post quem for the codex itself – which means one cannot exclude a production date around 650, for example. Only testing the ink can give you a date range for the production. That said, apparently there is a very slightly higher probability for the date to be the 5th century than the 6th (this is purely statistical, of course).