Much of the modern circulation of the Coptic manuscript fragments from the library of the Monastery of Apa Shenoute (or, alternatively, the White Monastery) still remains unknown to us. With some exceptions, we do not know exactly how the fragments came out of their cache, from the end of the 18th century onwards, or through which hands they passed before ending up in the collections where we can now access them. Although little explored, this topic is so generous that it can constitute at any time a separate field, apart from the philological endeavor of editing and translating the manuscripts into modern languages.

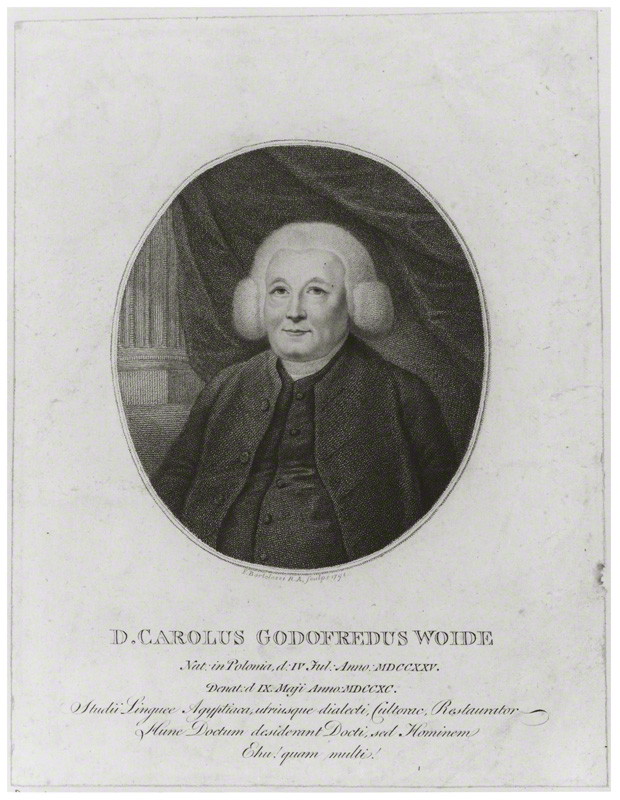

Here I would like to sketch, very briefly, an interesting episode from the modern history of a cluster of fragments from the Monastery of Apa Shenoute. During my readings, I became aware of the case of a certain Jean Dujardin, a French doctor who, at the beginning of the 19th century, quit his profession in order to learn Egyptian. At that time, Egyptology was the newborn baby of philology, due to Champollion’s decipherment of the hieroglyphs. Dujardin’s good knowledge of Coptic, which was surpassed, said one of his contemporaries, only by that of the great Étienne Quatremère, recommended him to the Minister of France for a scientific expedition to Egypt. The purpose of this expedition was to rectify the embarrassing penury of Coptic manuscripts in the French collections. France could not boast in that epoch with a collection of Coptic documents comparable to those that one could find in Italy (the Vatican collection of the cardinal Stefano Borgia or that of Giacomo Nani in Venice) or England (the British Library and the collection of Charles Woide in Oxford).

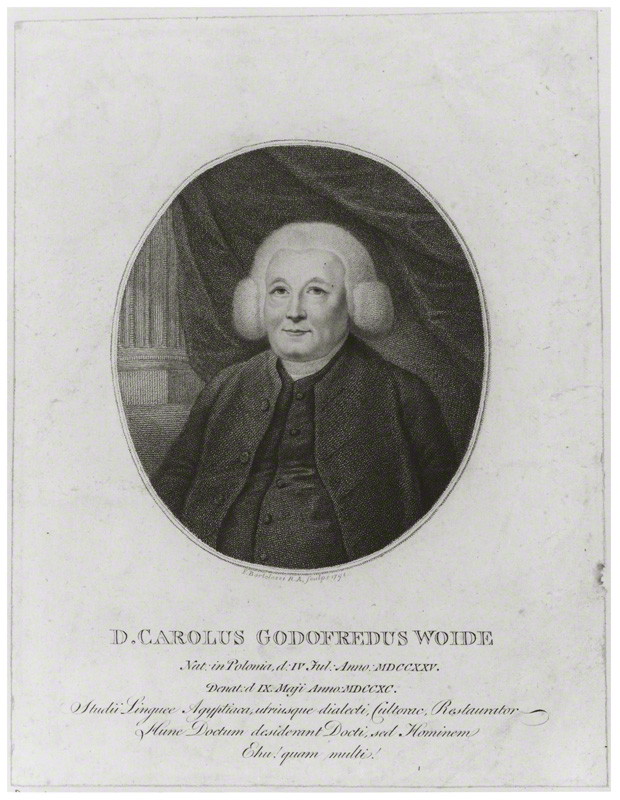

Portrait of Charles Woide. Copyright: National Portrait Gallery, London (source of the image)

Portrait of Charles Woide. Copyright: National Portrait Gallery, London (source of the image)

This was a reason good enough for the authorities to send Dujardin in 1838 in search of Coptic manuscripts in Egypt. Unfortunately, not long after his arrival there, Dujardin died of dysentery, which he contacted on the Nile. However, the sure thing is that, after less than a month spent in Cairo, he managed to acquire quite a large number of Coptic manuscripts, which he was supposed to bring with him to France upon his return. This is obvious from a report which Dujardin sent to France on July 3, 1838. The same year, an article based on this report was published in Nouvelles annales des voyages et sciences géographiques vol. 3/1838 (Paris: Librairie de Gide, 1838) p. 363-364:

He (scil. Dujardin) had collected from various individuals thirty manuscripts … some of which are in the memphitic dialects (sic! A.S.), others in the Sahidic dialect. Among these manuscripts, copies of which will be sent to the Minister, are: the Prophet Isaiah, the prophet Jeremiah (including Lamentations), Baruch and the Letter to the Jews taken captives to Babylon, the Book of Job, the first fourteen chapters of Proverbs, and fragments of the Books of Kings, Wisdom of Solomon, Ecclesiastes, etc.

The manuscripts in the Sahidic dialect were discovered by chance in a bundle of old parchments. These are the first two Books of Kings, a part of the Psalms of Jeremiah, of the Gospels of St. Mark and St. Luke, the Letter to the Galatians, the Acts of St. Andrew, of St. George, of St. Pteleme; the Life of St. Hilaria, the daughter of the Emperor Zeno, the Panegyric of the forty martyrs, fragments of St. Athanasius, St. John Chrysostom, St. Basil, etc. … During his stay in Egypt, he hopes to further increase significantly the mass of material that we already possess, in order to achieve the perfect knowledge of the Egyptian language. (Trans. from French A.S.)

For some reason, none of the manuscripts purchased by Dujardin has ever made it to France. Instead, the National Library in Paris possesses only his transcription of the material, made immediately after the acquisition.[1]

I am not sure what happened to the manuscripts of Dujardin after his premature death in 1838, but their description in the aforementioned report, however brief, allows us to identify their current location. Thus, the John Rylands Library in Manchester preserves in its rather small collection of Coptic parchments exactly the same works mentioned by Dujardin as being in his possession. I enumerate them here, together with their numbers in Crum’s Catalogue of the Coptic Manuscripts in the Collection of John Rylands Library, Manchester (1909):

Kings (Crum no. 2; 3 leaves); Jeremiah (Crum no. 8; 4 leaves); Gospel of Mark (Crum no. 11; 6 leaves); Gospel of Luke (Crum no. 12; 7 leaves); Galatians (Crum no. 14; 8 leaves); Acts of Andrew (Crum no. 87; 4 leaves); Martyrdom of George (Crum no. 91; 8 leaves); Martyrdom of Pteleme (i.e. Ptolemy) (Crum no. 92; 4 leaves); Life of Hilaria (Crum no. 96; 4 leaves); Panegyric on the 40 Martyrs (of Sebaste) (Crum no. 94; 8 leaves) sermons by Athanasius, Basil of Caesarea and John Chrysostom (Crum no. 62; 6 leaves).

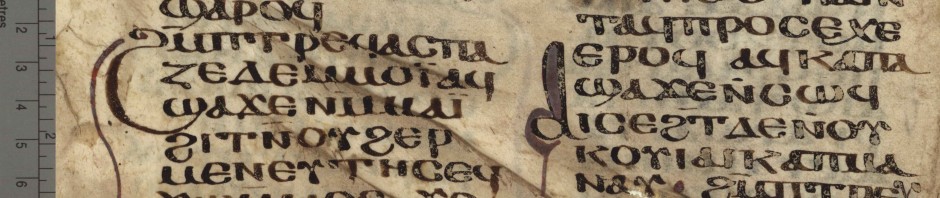

John Rylands Coptic 87, fol. 3v: the Acts of Andrew. One of the Coptic fragments in the John Rylands Library formerly in the possession of Jean Dujardin. Copyright: the John Rylands Library.

John Rylands Coptic 87, fol. 3v: the Acts of Andrew. One of the Coptic fragments in the John Rylands Library formerly in the possession of Jean Dujardin. Copyright: the John Rylands Library.

As we can see, all the Sahidic works mentioned by Dujardin are recoverable in the John Rylands collection. Although the final proof will come only after we will compare the transcription of the fragments made by the unfortunate explorer with the originals in Manchester, I would say that we already have good enough reason to believe that they are the same documents.

A further argument in this direction is supplied by what Walter Crum already knew about the John Rylands collection when he catalogued it. The collection formerly belonged to the Earl of Crawford, who bought an important part of them on June 16, 1868, at Sotheby’s. This lot of manuscripts was owned before by Henry Tattam, but his family decided to sell it in the auction six months after the death of the owner. It is noteworthy that, with the sole exception of no. 62, Crum managed to ascertain that all the other call numbers given above came from Tattam’s collection. Moreover, among the Crawford Bohairic manuscripts, formerly owned by Tattam, Crum nos. 417-418 contain exactly the same sequence of Biblical books as given by Dujardin. This makes me believe that not only the Sahidic fragments in the possession of Tattam came from Dujardin, but also some of the Bohairic codices.

I think it is likely to infer that Tattam’s collection was actually the one formed by Dujardin during his first and last journey to Egypt. What I can only guess is that some avaricious person stole Dujardin’s manuscripts after his death and sold them further. Thus, the documents never arrived to France, as they were supposed to do, but they ended up into Tattam’s hands, who was at that time travelling to Egypt and Middle East for the same purposes as Dujardin. The memoirs of this voyage were recorded by Tattam’s niece, Miss Platt, in her Journal of a Tour through Egypt, the Peninsula of Sinai, and the Holy Land, in 1838, 1839 (2 vols., printed for private circulation by R. Watts, 1841-1842). From her notes, it is clear not only that the English travellers knew about Dujardin and his unfortunate destiny, but also that they were aware that he collected Coptic manuscripts. At one point, it becomes apparent that Tattam was trying to track down these manuscripts. Here is what Miss Platt wrote in this regard:

Friday, Nov(ember) 9 (1838): … (Tattam) called … on the French Consul; with whom, and Mr. Fresnell, he went to the Frank (i.e., Catholic) Convent, to see M. Dujardin’s MSS.; but found he had only copied the first nine chapters of the Book of Job, a chapter of the Book of Kings, and one or two of the Psalms. (Platt, Voyage, vol. 1, p. 94)

It is clear, thus, that Tattam was looking for Dujardin’s manuscripts, but he managed to acquire them only after this date (i.e. November 9, 1838).

These facts reveal that the John Rylands Coptic parchments are actually part of one of the earliest collection of such documents, formed in the late 1830s. A collection which was built upon the sacrifice of a little-known pioneer in Coptology: Jean Dujardin.

[1] Bibliothèque de l’Ecole des chartes vol. 61 (Librairie Droz : Paris, 1900) p. 53 : “20391-20393. Papiers de Jean Dujardin, chargé de mission en Égypte (1838) : Copies de manuscrits coptes, de papyrus égyptiens et grecs et d’inscriptions hiéroglyphiques. – Une notice des pièces est en tête du premier volume.”; Nouvelles acquisitions du Département des manuscrits pendant les années 1900-1910 (E. Leroux : Paris, 1911) p. 53.